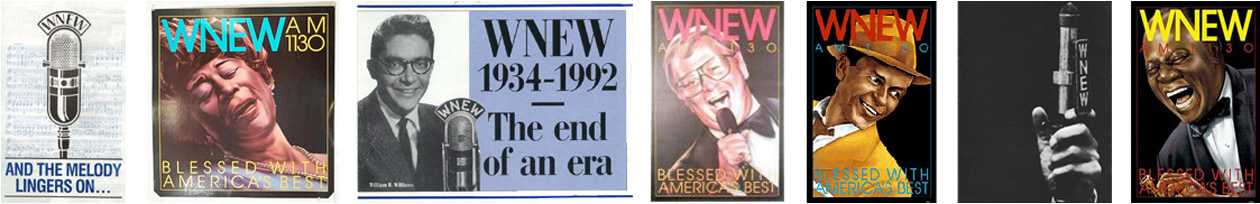

WNEW Fading Into Radio History

By Paul D. Colford

STAFF WRITER

New York, Dec. 2 —WNEW-AM / 1130 the 58-year old outlet for the music of Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, Mel Torme and America’s greatest songwriters, died today after a long illness marked by financial losses, anemic rating, schizophrenic programming and the dismissal of practically every personality who made it special.

The end for the long-deposed monarch of New York stations came at 10 a.m. when singer Tony Bennett was to help The New York Times Co. convert WQEW, at 1560 AM, into a new haven for pop standards.

TO BE FAIR, the ghost of WNEW will limp along for another week or so with music-by-day and Larry-King-by-night before a new owner completes its purchase of the station and launches a 24-hour business format on 1130 AM. But the death watch that continued through management twists and ownership turns in recent years effectively ended this morning with the sign-on of its successor.

The startup of WQEW is a happy ending for those New York listeners who would have lacked an outlet for Gershwin and Bennett. At the same time, the demise of WNEW-AM has prompted wistful recollections of a once-great station.

“There’s been a great deal of gnashing of teeth in recent years because WNEW really occupied a special place in people’s psyche,” said WOR general manager Bob Bruno, who was WNEW’s program director in the mid-1970’s. “This wasn’t just another radio station. It represented culture, sophistication, and people felt like they were with the stars when they listened to the personalities who played the music. As a listener, you got to be on the inside.”

Generations of listeners got their first taste of the great composers, bands and vocalists from WNEW-AM. Indeed, they were hooked on the station’s sounds even after television became the dominant entertainment medium.

Bloomberg Communications Inc., the buyer that will install the business format, is paying nearly $13.6 million for what was worth an estimated $25 million in 1962. In that year, the station raked in more than $7.1 million in advertising, tops in the nation, and took the unprecedented step of dropping its national ad representative. Instead, the story goes, the station’s own sales people would come in, hang up their coats and simply start taking sponsors’ calls at 9:00 am.

WNEW hatched the idea of a disc jockey when staff announcer Martin Block started to play records during breaks in the station’s 1935 coverage of the Lindberg-kidnapping trial of Bruno Hauptman. Soon afterward, he presented records in an afternoon theater of the mind that was called “The Make-Believe Ballroom.” This writer’s mother recalls coming home from high school with her girlfriends, pushing the dining-room table against the well and dancing to the tunes of Glenn Miller and Sammy Kaye that Block had on his turntables. His style at the microphone was so warm and intimate that my grandfather, a hard-to-impress Irish railroad man, would say, “Open up the door because that fella’s coming right in.”

From 1946 to 1963, Dee Finch and Gene Rayburn enlivened mornings with “Anything Goes,” poking fun at their commercials from time to time. Gene Klavan, a master of voices and inspired anarchy, then worked alongside Finch before going it alone in 1969. The popular William B. Williams, who sounded so casual that he might have been hosting “The Make Believe Ballroom” stretched out in bed, was champion and pal of the singer he called “Francis” and “Chairman of the board.” Ted Brown, he of the cornball jokes and insatiable girl hunger, stood in amusing contrast to the intellectual Jonathan Schwartz, a former rock jock, who brought a freewheeling FM sensibility to the AM station, when he started doing weekend shows in 1971 — shows that he will now host on WQEW.

In news coverage, too, WNEW set the standard. In 1942, WNEW was believed to be the first station to break for hourly newscasts as prepared by the broadcast desk of the Daily News. In 1958, the station ended its association with the tabloid and spent lavishly to staff a homegrown news department with 13 reporters and rewrite men — a number that would more than double in time and seem all the more remarkable when viewed in today’s news-stingy radio times. WNEW’s own reporters went to Africa to interview Albert Schweitzer, they roamed the South to size up the civil rights movement, they broadcast from Vatican Square and Cape Canaveral. Reid Collins, Ike Pappas, Edward Brown and Jim Gordon were among those who told their stories on the hour and half-hour.

As late as the mid-1980’s, a listener could still sample the sophistication that was WNEW’s trademark. Ratings had declined from the glory years, as they had for all AM music stations, but WNEW averaged a respectable 3 share (percent) of the New York audience by remaining true to the American songbook. At no cost, a listener could relax in the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel at midday and watch Williams do live broadcasts alongside Keely Smith and other great singers who weren’t born yesterday. If it was Matinee Day, a visit to Charley O’s at Shubert Alley would find “Mr. Broadway,” afternoon disc jockey Jim Lowe, chatting it up with Cleo Laine and other performers, or persuading the great Sylvia Syms to get up and hush the house with her songs. Schwartz and resident pianist Tony Money would bring Julie Wilson, Helen Merrill, Maureen McGovern and other cabaret stars into the studio for still more conversation and live vocals.

But the mid-80’s also was the beginning of the end. In 1986, billionaire John W. Kluge sold WNEW and eight other radio stations owned by his Metromedia Inc. for $285 million. Almost immediately afterward, the buyers, burdened with debt, slashed all but the morning newscasts, canceled the live shows and broke up the music late at night with a syndicated talk program featuring psychologist Toni Grant. An evening sports program seemed even more glaringly out of place, and Steve Allen was paid a pile to do a talkative daytime broadcast that evolved into an inside joke among him and his friends.

Lowe, who was dismissed in 1987 after a total of two decades with WNEW, said from his home in the Hamptons that the new management was unwilling to enhance and protect the station’s 3 share and created the hodgepodge in a bid for revenues that alienated the core audience. “If you’re going to play Chinese bells on the air, that’s fine, but you’ve got to do it for twenty four hours,” he said.

Ratings weakened and WNEW was acquired in 1988 by investor Robert f. X. Sillerman, who then sold half to Westwood One Inc., based in Culver City, Calif. With an aging audience and meager ad revenues outside of the station’s New York Giants broadcasts, Westwood management became little more than a caretaker. It fired supervisors, disc jockeys and, finally, Mike Eisgrau, the last newsman, in what seemed an obvious effort to stem losses and make the payroll lean enough to attract a buyer. The spring rating ranked WNEW a dismal 20th with a 2 share, so that the August announcement of Bloomberg’s purchase signaled an end to the patient’s misery. Sillerman conceded that WNEW was not making money. He added, “It was acquired when there was a little more optimism about its future.”

In the end, The New York Times Co., which owns WQEW, wanted nothing from the “estate” of WNEW. No records, no call letters, no jingles. Only Schwartz. “It really is an American radio tragedy, because it’s symptomatic of what has happened to the industry over the last two decades,” Bruno, of WOR, said: “The owner-operators have gotten out of the business and a lot of the product is slowly being eaten alive…Now, this thing is being buried.”

——-