New Yorks Daily News 3/17/04

By DAVID HINCKLEY

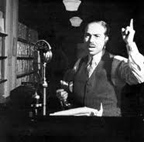

As the only station broadcasting from inside the New Jersey courtroom where Bruno Richard Hauptmann was on trial for the kidnapping and murder of Charles A. Lindbergh’s infant son, New York radio station WNEW had itself a huge coup. It also had a problem.

WNEW’s on-site reporter and engineer were not set up to carry play-by-play coverage of the trial, only periodic bulletins. But because public interest was so high, WNEW didn’t want to switch to, say, an orchestral remote that would prevent the station from using its logistical advantage to break in with each shard of news.

A month or so after the trial began in January 1935, a solution to this dilemma was proposed by a low-level employee named Martin Block, a good-natured, ambitious fellow with slicked-back hair and a pencil-thin mustache in the sophisticated style of the mid-’30s.

Block was the warm body sitting at the microphone back in the WNEW studios at 501 Madison Ave., and his suggestion to WNEW general manager Bernice Judis was that he fill the downtime by playing records.

Something that, in early 1935, respectable radio stations hardly ever did. For a station like WNEW prided itself on live music. Records were lazy and redundant. If a listener wanted a record, he or she would buy it, not turn on the radio.

Ironically, many artists felt the same way for exactly the opposite reason. They were afraid that if fans could hear their recordings on the radio, those fans would not buy records any more.

But WNEW was stuck, Block persisted, and on Feb. 3, Judis told this $25-a-week part-time staff announcer pest to go ahead and do it. Block faced one final hurdle, which was that WNEW didn’t own any records. So he trotted out to the nearest Liberty Record Shop and bought five of them, all by Clyde McCoy. He also launched his plan, which basically was to demonstrate that records were the future of radio.

Block, A New York kid who was born to sell, had started his career peddling razor blades and potato peelers off a sound truck on Broadway. By the early 1930s, he had moved to the West Coast, where he got his first radio job with a two-bit outfit in Tijuana and then worked his way up to Los Angeles. One of the big shots in L.A. then was Al Jarvis of KFWB, who played records regularly and around 1932 began calling part of his show “The World’s Biggest Make-Believe Ballroom.” He would play several records in a row by the same artist while painting a picture for his listeners of this music wafting over a sparkling dance floor.

Now, three years later, Block envisioned crafting his WNEW show on the same model, and that was fine with Judis. The problem was the sales staff, which told him no sponsor would buy time for a program of prerecorded music. So Block went out and found his own sponsor: the makers of Retardo pills, a harmless if useless weight loss gimmick that sold for $1 a box. “Ladies,” Block would purr into the microphone, “be fair to your husband by taking the reducing pill.”

A week later Block and WNEW claimed Retardo had received 3,750 responses, and soon enough there was little doubt the show was a hit. Within a few years, “The Make-Believe Ballroom” commanded a remarkable 25% of the radio audience. Block became friends with stars like Glenn Miller, who needed him to play their records, and for his sponsors he claimed to have invented two of the most popular cigarette slogans ever: “ABC: Always Buy Chesterfield” and “LS/MFT,” for “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.”

The first theme of “Make-Believe Ballroom,” naturally, was a Clyde McCoy number, “Sugar Blues.” That was bumped by Charlie Barnett’s “Make-Believe Ballroom,” which in turn yielded to Miller’s “It’s Make-Believe Ballroom Time.” Block co-wrote the lyrics to that one and, after Miller was killed in a plane crash in December 1944, Block announced that “Make-Believe Ballroom Time” would remain the theme forever.

“Make-Believe Ballroom” went into national syndication in 1940, and by the end of World War II, Martin Block was making $22,000 a week. Then, in August 1946, KFWB announced that Block was coming west to take over the show there. Almost a year of headlines later, in June 1947, he did. And he promptly tripped over his shoelaces.

Angelenos considered him an obnoxious, arrogant, know-it-all New Yorker and tuned him out by the millions. By the fall of ’48 he was ready to return to New York, to take advantage of the new television opportunities. He tried to. But he was not a TV guy, and soon he was back at WNEW. In 1954, he jumped to ABC radio and, when the tidal wave of rock ‘n’ roll crashed onto the shore, he jumped to WOR, where he did weekend shows until his death in 1967. WNEW continued the “Make-Believe Ballroom” with a string of other hosts. Descendant programs are heard to this day.

While Martin Block may have felt his real calling was to sell diet pills and Edwin cigars, many radio people feel he was to radio what Bing Crosby was to recording: the first to introduce an intimate, personal style rather than a disembodied voice of authority.

Whatever his legacy, the Make-Believe Ballroom was the best dance value in town.

NY Daily News

Letter to the Editor

Making believe

Flushing: In his otherwise fine Big Town Songbook article on the early history of radio station WNEW (“Future of Radio: Martin Block Makes Believe,” March 17), David Hinckley does a disservice when he comments that after Block, the “Make-Believe Ballroom” program was continued with “a string of other hosts.” Those hosts included Art Ford, who succeeded Block in 1954 and who in turn was replaced by William B. Williams, who hosted the show from 1958 until his death in 1986, except for the brief period when the station changed formats.

Let’s not give short shrift to legends like Willie B.

John A. Drobnicki