The New York Times

Sale of WNEW-AM Could Replace Sinatra With Stock Reports

By James Barron

Sunday, August 16th, 1992

Cirino Colacrai remembers when a few minutes on WNEW-AM meant the difference between a hit and a flop. Like the Brooklyn Dodgers and the old Pennsylvania Station, those days are gone forever, and music on WNEW-AM — any music, except for the jingles in commercials — may soon be gone, too.

The station is expected to switch from the pop charts to the stock charts once a $13.5 million deal to sell it to a financial-information entrepreneur goes through. It is a change that Mr. Colacrai, a songwriter, is not looking forward to.

“The guys were classy, the deejays,” he said. “They gave you nice interviews. It was a prestige station. It wasn’t the Alan Freed show or Dick Clark. This was one step above.”

Alan Freed is widely credited with popularizing rock-and-roll, and Dick Clark presided over “American Bandstand” as television evolved from live black-and-white to videotape and living color.

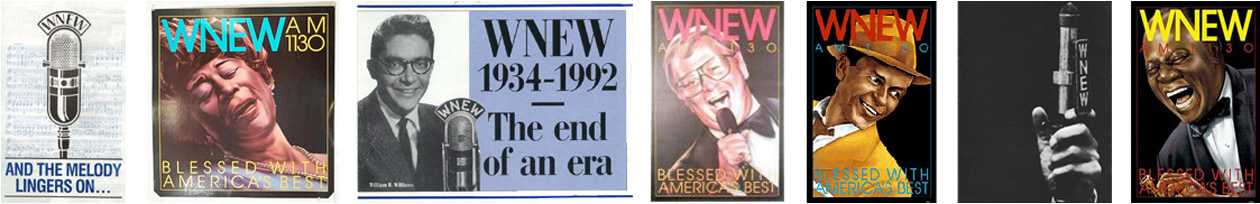

But WNEW-AM was a taste maker, from the days when Walter Winchell improved on the names of shows on the station (he suggested changing the all-night show from “Stan the Milkman” to “Milkman’s Matinee”) to the days of personalities like William B. Williams, whom Frank Sinatra credited with resuscitating his career. It was Mr. Williams who gave Mr. Sinatra the nickname of “chairman of the board.”

Soon though, the station’s format is likely to change. The WNEW-AM owners, Westwood One and Robert Sillerman, said on Friday that they had agreed to sell it to Michael Bloomberg L.P., which supplies financial data to Wall Street traders.

The station is expected to broadcast up-to-the-minute reports on the London and Tokyo stock markets. They rise and fall before most New Yorkers rise and shine, or try to.

“If people would really rather listen to business news than Sinatra, then I’m glad I left the city,” said Wilfrid Sheed, the essayist and novelist, who lives on Long Island. “This is the music people are lining up around the block to hear. Any time Michael Feinstein is rumored to be giving a concert, it’s an instant sellout.”

WNEW-AM made its name in the 1930’s and 40’s with pop songs and swing bands, creating a niche in the days when big network-owned stations had whole orchestras on standby, a luxury non-network stations could not afford. And in the 1960’s it was overwhelmed by rock-and-roll, which lured WNEW-AM’s younger listeners — the ones advertisers prize the most. But even as ratings dwindled in recent years, the audience that remained was loyal.

“The stuff they played was the music I grew up with,” said George B. Eager, a retired Princeton University official. “The individual announcers were extremely well informed, like fans themselves. And there was enough news on there to keep you well informed.”

From bars to barbershops to boardrooms, WNEW-AM was long the station of choice for many New Yorkers. “I understand that all the Mafia guys listen to it, too,” said Lyle Stuart, the publisher of books on everything from sex to the C.I.A. “John Gotti has it turned on.”

In some ways, WNEW-AM had come to be about history, the history of radio and the history of the American popular song. But Gene Klavan, an on-the-air personality at WNEW-AM for more than 15 years, said the station’s programmers “had locked themselves into a period of becoming a music museum.”

“I’m sorry it had to happen,” he said of the switch to business news, “but AM radio has to find new ways to keep its viability, and I think this is probably a pretty good idea.” Fervent Opposition

Mr. Klavan’s opinion is one that Sidney Zion, the journalist and lawyer, most decidedly does not share. “If this were a classical music station, they would never get away with it,” Mr. Zion said. “Where are the politicians and civic leaders when Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald are being run out of town by stock quotations?”

Few other stations have had the kind of history that WNEW-AM has had. Longtime listeners maintain that WNEW-AM was where disk jockeys were invented, though the term is credited to Winchell — and he did not mean it as a compliment.

The first disk jockey, Marvin Block, was hired not as an announcer but as an advertising salesman. But Bernice Judis, then general manager of the station, declared that he had “the sexiest voice in America” and put him on the air at $25 a week. In 1935, she sent him to cover the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptman, who was accused of kidnapping and killing Charles A. Lindbergh’s son. He set up his microphone in a men’s room at the courthouse in Flemington, N.J., and began worrying about filling the time between bulletins.

The big network stations had staff musicians standing by who could start playing on cue. Mr. Block suggested playing records instead — a novel idea in the days of low-fidelity 78 R.P.M. disks. ‘Make-Believe Ballroom’

But not until the trial was over and Mr. Block went to California for a vacation did he realize the idea’s potential. On a car radio, he heard a Los Angeles announcer improvise after a dance-band broadcast from the Palomar Ballroom was canceled. The announcer, Al Jarvis, played a record by the band that had been scheduled for the Palomar and said that he was at “the make-believe ballroom.”

There was canned applause between records, and he talked about the glimmering chandeliers, the shiny bandstands and the sophisticated crowd. The broadcast had a you-are-there reality even as he reminded listeners that he was making it all up.

Back in New York Mr. Block told Miss Judis, “That’s the way to program records.”